The perfect site for a volcanology class? The North Carolina Museum of Art.

Volcanologist Arianna Soldati held a class session at the North Carolina Museum of Art last semester, a trip that emphasized the blurred yet beneficial relationship between the arts and sciences.

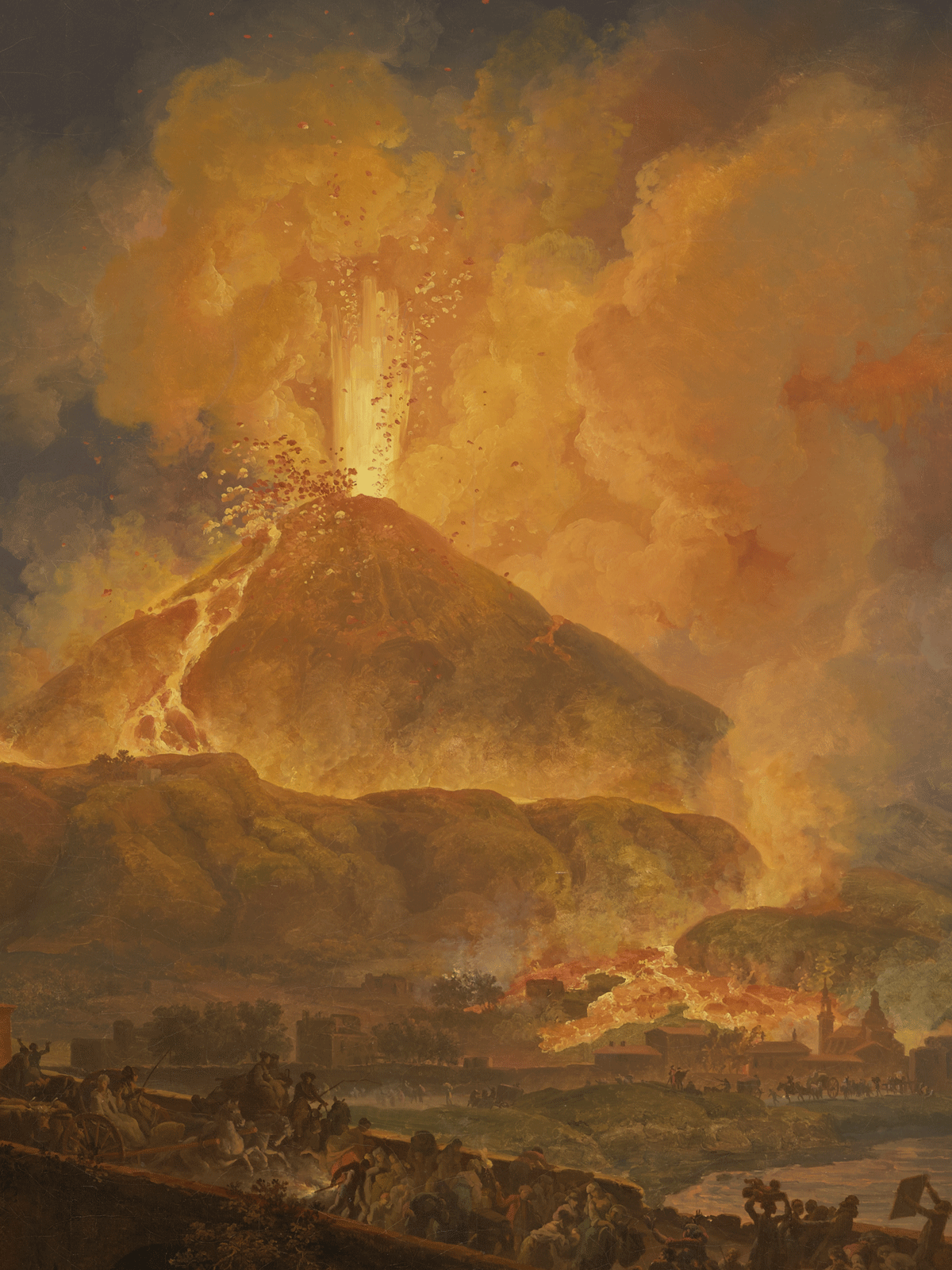

North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh; Purchased with funds from the Alcy C. Kendrick Bequest and the State of North Carolina, by exchange, 82.1

Volcanologist Arianna Soldati held a class session at the North Carolina Museum of Art last semester, a trip that emphasized the blurred yet beneficial relationship between the arts and sciences.

At the museum, students in MEA 493 and MEA 592, Special Topics in MEAS and Earth Sciences, learned about the historical perceptions and depictions of volcanoes. Soldati challenged them to reflect on how that history can shape modern understandings within the volcanology field.

After a brief lecture, students crowded around a striking 18th-century oil painting at the museum of a volcanic eruption, titled The Eruption of Mt. Vesuvius. The more than seven-foot-wide piece was painted by Pierre-Jacques Volaire, a painter who produced several dozens of pieces showcasing Mount Vesuvius’ eruptions, which he would have directly observed while he was living and working in Naples.

Read the following Q&A session with Soldati to see this work of art through the eyes of a volcanologist.

Q: What story is this painting telling? Walk us through what it shows.

There are two main aspects that come together in this eruption. Of course, very predominant is the eruption of Mount Vesuvius itself in the background, but also in the foreground we see how the eruption impacted the people of Naples, the people living nearby. So, we have both a scientific and a social aspect coming together into this painting.

If we start by observing the eruption in the background on the left of the painting, we see a Mount Vesuvius that is behaving in a completely different way from what we all probably picture when we think of Mount Vesuvius. Most of us think about the 79 A.D. eruption, the one that destroyed Pompeii and Herculaneum. That type of eruption is explosive, with a big ash column that reaches all the way up into the stratosphere, with ash and hot gas then rushing down the flanks of the volcano and destroying everything in their path.

But, this is not what the artist is representing. In the 18th century, Mount Vesuvius did not erupt that way. The volcano was in a very different phase, and it was instead mainly erupting effusively, meaning that instead of producing columns of ash, it was mainly producing lava fountains and lava flows — molten rock that flows down the flank of a volcano at a few meters per minute to a few meters per second.

Let’s talk about the social aspect of this painting. This is really exceptional because we are at a time in history when we are observing a change in how the reaction of people is being portrayed in the face of volcanic eruptions.

Now, this is a slightly earlier painting, so most of the social focus here is on people of humble means that live nearby the volcano and are terrified by its activity. People are clearly self-evacuating. They are in carriages trying to escape, and their humble condition is highlighted by the fact that most of them are barefoot and are carrying their few belongings on top of their head, for example. We also see that people are praying to San Gennaro, who is the patron saint of the city of Naples. so that he can intercede with God for the end of the eruption.

Now, if we were just a few years later, we would be seeing a different scene because at the time, we also had people who took part in the Grand Tour, which was this amazing trip throughout Europe that people who were well off got to take in their youth. They would have been admiring the volcano. There are many paintings by Pierre-Jacques Volaire, just a few years later than this one, and they depict noble people being up high, close to the volcano in their beautiful and luxurious clothes, looking at it and admiring it.

So, this is the shift from people being scared and frightened and somewhat superstitious, to people beginning to appreciate the powerful volcanic phenomenon and beginning to interrogate themselves about what its true causes might be. However, the social divide remains because it is only the richer people who are able not to be frightened by the volcano, but rather admire the sublime aspect of its eruption, whereas the populace remains scared and impacted negatively by these eruptions.

Q: Could you talk a little bit more about this kind of period or genre of art? How does it differ from art movements that came before it or art movements that came after it?

The history of volcano representations in art is quite interesting and brief. Up until the Middle Ages, volcanoes were considered unsuitable art subjects. Even when they were represented, they were only there to indicate some sort of evil, some sort of punishment — it was devils, and it was hell. They were allegorical paintings. The focus was not on the geologic phenomenon.

Then, when photography started becoming more widely available, those who wanted to take home a memory of the amazing phenomenon that they had just witnessed would buy a photograph. So really, the golden era of realistic volcanic paintings is all squished in a couple of centuries: 17th to 18th century.

These paintings have a really interesting intersection with the birth of scientific societies. The way it used to work was that if you were part of a scientific society and you took a trip somewhere and conducted an investigation, then you would write a letter back to your society describing what you had learned. It became quite fashionable to engage artists to produce scientific illustrations of the phenomenon at hand to send back because a picture is worth 1,000 words. It would be incredibly difficult to imagine what an eruption looks like if you hadn’t seen one before.

So, we have this really interesting intersection of art and science. But, we also have to remember that although we can learn a lot from these realistic paintings, art works are not always just primary sources. Sometimes, the painter will add some elements that he thinks are of particular interest. He will blend together phenomena that he would have observed at different times.

For example, in the case of this particular painting, we know that most likely the painter did not observe this eruption at night, or at least did not make his sketches for the painting at night. We know from his letters that he would climb up the volcano to observe the eruption every day, during the day, for many months in a row, and then he would work back in his studio to finish up the painting at night. And yet, this is a night view — this is just because an eruption at night is just that much more spectacular, right? So, we do have to take everything we’re seeing with a little bit of a grain of salt because some elements might have been added or changed just to make the painting more interesting.

Q: Where do you draw that line, then, between using this as a scientific document versus figuring out what the artistic choices are?

Drawing the line between what is the geological reality that is being depicted and where does the artistic license start coming into play is really difficult. I think that the best way to go about it — if we are so lucky, as we are in this case — is to look at multiple sources. See what elements are always present, and which ones change in a way that’s maybe not so coherent.

Also, it’s really important to know that context, know who the paintings were made for. Often these paintings were made on commission, and so perhaps there was a particular aspect that art patrons wanted to have emphasized. This is something that historians who focus on that particular historical period would know and might be able to use to shed light onto this particular aspect.

The other part is that, as geologists, we can use the geologic record to learn about what type of volcanic activity was common at the time. So, we can ground truth with the geological record; the deposits, the ash that would have fallen and the lava flows that would have been in place — those are still there today. So, we can go look and see if they’re really where the artist depicted them, and we can date them and see if they were really in place at the time when the artist is representing them as active and flowing.

Q: Looking at this painting from a volcanology standpoint, what can you learn from the painting?

I think that the main takeaway from this painting is that volcanoes do not always, throughout their entire life cycle, erupt in the same way. It is really striking to see Mount Vesuvius emplacing lava flows; this is simply not the mental picture that we all have of it, but this is clearly what was happening during the 18th century.

Then, although I’m a volcanologist and a scientist, I think that perhaps the most interesting part of the painting is actually the social aspect, the reaction of the people. It really highlights how whether we’re in 18th-century Southern Italy, or in the 2000s in the United States, when there is a lava flow that is threatening our town, ultimately, we all experience fear for what is coming, and for the impact that it is going to have on our life. There’s this very human element that reminds us that despite the interest and the beauty of the eruption, there are real consequences, and people try as best as they can to escape or mitigate them.

Many paintings like this one were painted on commission, and they were sold by the people who went on the Grand Tour. It’s really interesting to me that these noblemen — who themselves had never before seen an active volcano — it’s really interesting to me that they would be so fascinated by it. It’s really incredible to see volcanoes rise to the level of popularity that they did, becoming a fixed stop in this Grand Tour together with famous churches in Rome. It’s really like a natural, geological phenomenon being elevated to the same level as human art and architecture, and I don’t take this for granted.

Q: Does this kind of knowledge of how things might have played out in the past contribute to modern — or even future — understandings of Mount Vesuvius or volcanoes in general?

Absolutely. Knowing the volcanic history of a particular volcano is the starting point for forecasting what its activity might be in the future. For example, when in 2018 we had a little bit of explosive activity out of the summit of Kilauea Volcano in Hawaii, a lot of people were saying that this behavior was completely uncharacteristic and like nothing we had seen before. Sure — in our lifetime. Over the past 50–60 years, Kilauea has mainly had effusive eruptions with lava flows. But actually, as geologists, if we look at the geologic record, we know that Kilauea has erupted explosively many, many times before. So, the types of volcanic hazards that come with that type of activity are something that we need to be prepared for.

Likewise for Mount Vesuvius: knowing that it is not always going to erupt in the worst-case scenario — the explosive, completely devastating eruption like it did in 79 A.D. — but that smaller lava flow-producing eruptions are also possible is really important. When we think about preparing for future eruptions, as volcanologists, we do not advise to be prepared for the worst-case scenario. We try to be ready for the most likely scenario, and so it’s really important to have an overview of what the activity of the volcano has been throughout history, and not to focus on only the most eye-catching and devastating episode.

Q: So, this is just another piece to the puzzle in terms of building out that history of certain places?

Yes, absolutely. It reminds us that whatever type of activity was most common at the time and was being represented in art, and described back home at the end of a journey, is a piece of the actual geologic history of the volcano and could very well be happening again right now. Naples is extremely populated, and there is great worry for what would happen in case of an eruption.

Each type of volcanic eruption has its own unique risks. I would say that in terms of threats to human life, lava flows are way less dangerous. By and large, lava flows can simply be out-walked. This is not the case when we have an explosive eruption in a pyroclastic flow that is hot ash and gas that’s moving at hundreds of kilometers per hour. There is no getting out of the way or or surviving that — Pompeii and Herculaneum were both destroyed by pyroclastic flows. If we talk about property and infrastructure, it’s a completely different story. A lava flow is going to be just as devastating to a house as a pyroclastic flow would be.

The last time that Mount Vesuvius erupted was during World War II, and lava flows were one of the main manifestations of that eruption, and there are photographs of American soldiers roasting marshmallows on them. So, it’s important to remember that there can be a variety of ways in which a volcano erupts, and it’s good to know what the complete story is.

Q: You had your students practice looking at this painting and applying their knowledge of volcanoes. Why is that kind of exercise important?

Looking at the painting and being able to key in on what phenomena and hazards are being showcased is really important because it’s a different way of practicing observational skills. Volcanology is very much an observational science. Yes, we have a lot of instrumentation that we can rely on, but observing directly an eruption remains a primary way of understanding what is happening.

Because with this class we don’t have the opportunity to go out to the field and work on an active eruption, it’s important to use a variety of means to practice the skill set. We use virtual reality, but we also look at how eruptions are depicted in Hollywood. And, we look at how they’re depicted in art, and how they’re described in literature because it’s all different ways of practicing making those observations that are so important for the advancement of technology.

Q: It sounds like art makes better scientists.

Absolutely, art does make better scientists! Plus, let’s think about the importance of making field sketches. We all remember, if we’ve been in geology, our field book where we’re told to make a sketch of what you’re looking at. It starts with being able to make the observation, deciding what is important to represent in your field book. I think it’s a very, very important skill.